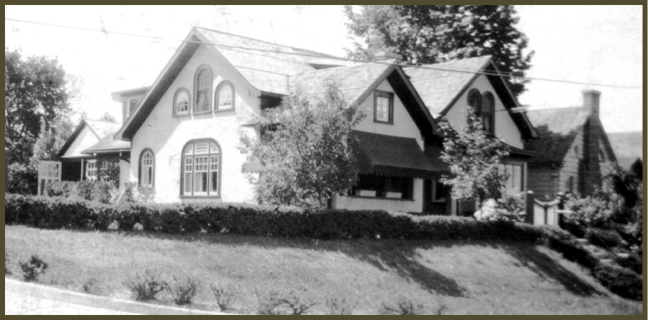

JDM HOMES

UTICA, N.Y. --WHERE HE LIVED FROM AGE 10 TO LEAVING FOR COLLEGE..

On the left, at the top near the gable end, is the room where he spent the year in bed while recuperating from scarlet fever. and also mastoiditis . He read a lot during that time.

9 Beverly Place

Utica, N.Y.

(built around 1923)

This picture shows the home in June, 2009. It is remarkably unchanged. A nice home, and large for its time (built in 1923).

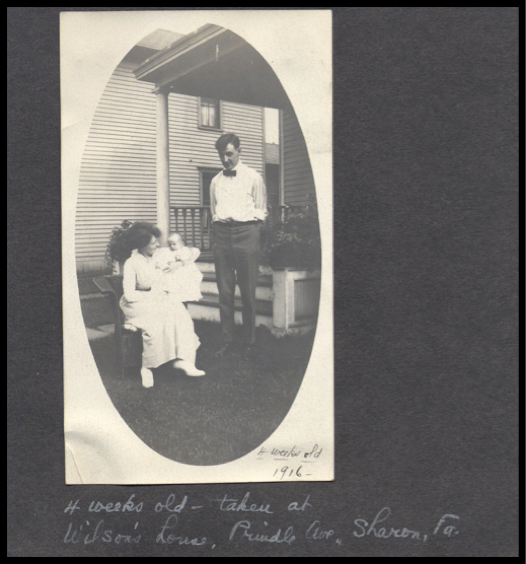

Eugene and Marguerite (Margie) Macdonald, and John Dann MacDonald, aged 4 weeks.

Margie, Eugene, and JDM

JDM around 1918-19

Grandfather Dann ( on his mother’s side) JDM, and father, Eugene. Dann was a member of Theodore Roosevelt’s hunting parties on several occasions.

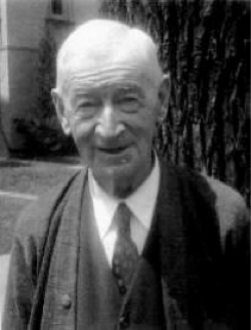

Grandfather Hugh MacDonald

in 1950

*************************************************************************************

“Why detective Travis McGee spent time on Bleecker Street”

By MALIO CARDARELLI

Utica Observer-Dispatch

Posted Aug 27, 2007 @ 08:06 AM

This column has celebrated a number of artists and musicians, mostly the latter, but never a novelist.

It's not that the Utica area has never had a notable one, nor is it due to lack of esteem for that form of creativity. Instead, it might simply be something overlooked. Nevertheless, it's about time a writer is herein chronicled.

John Dann MacDonald was born July 24, 1916, in Sharon, Pa. His father, Eugene, took a finance position with the local Savage Arms Co., so the family moved to Utica when John was 12 years old. He went to local schools including Utica Free Academy.

The MacDonald family lived at 9 Beverly Place on a small island that separates lower from upper Beverly Place.

After his 1933 graduation from UFA, John furthered his education at the Wharton School of Finance at the University of Pennsylvania, then at Syracuse University, where he earned his bachelor's degree, and finally at Harvard for his MBA. It was while at Syracuse that he married his lifelong partner to be, Dorothy Prentiss.

Subsequently, he went into the military, writing regularly to his wife. Just for a change, instead of a letter, he once sent her a short story, which Dorothy submitted to a magazine for publication. It was accepted for the sum of $25, not too small an amount in the 1940s. When he was discharged in 1946, he worked for a brief time for the Utica Chamber of Commerce with an office on Elizabeth Street near Grace Church.

However, John's love was writing, so the decision to try doing it full time came easy, especially with a cushion of four months' mustering-out pay from his army post. Of that time, John once said:

"During those months, I wrote over a quarter of a million words of finished manuscript all in short story form. I kept from 30 to 40 stories in the mail at all times. I worked 14 hours a day, seven days a week ... one learns by writing," MacDonald noted. "

That indefatigable dedication paid off, as acceptance after acceptance of his submissions were received, causing the young author to believe he was able to make a long-term living from his creations. That he certainly did.

In his lifetime, in addition to many short stories, he authored some 77 novels of drama and mystery, many that became movies such as "The Executioner," filmed as "Cape Fear," and "Condominium," later adapted for television. His most popular work was a mystery-detective series with a private detective, Travis McGee, who appeared in more than 20 of his works. More than 70 million copies of his books were sold.

And it isn't unusual for his characters, including Detective McGee, to roam around the Utica area on their adventures. even having dinner at Grimaldi's on Bleecker Street with his sidekick, Meyer, where they each began with an extra-dry martini and later with Valpolicella wine served with their dinners. The surroundings are described including Chancellor Park, but not by name, west of the restaurant.

This gives testimony to MacDonald's fascination with this region, an appeal made even more evident by his the summer residency at Piseco Lake in the Adirondacks, while his permanent home was in Florida. His Piseco Lake cottage is mentioned frequently, as is Utica, in his book, "A Friendship," a rare nonfiction work that assembled MacDonald's letters to and from Dan Rowan, of TV's "Rowan and Martin's Laugh-In" fame.

Both his mother and his sister continued living here, even after the death of his father, causing him to be in Utica for visits and to purchase items when he stayed at his Piseco Lake cottage.

Utican Keith Caulkins, once a customer relations representative for what then was Business Services Co. in North Utica, remembers going up the MacDonald place several times each summer to assure the author was happy with his copy machine provided by Business Services.

"It was a nice cottage, not elaborate but comfortable, at the end of the lake in a remote area with a gorgeous view of the lake and the surrounding mountains," Caulkins said. "I loved going there because the MacDonalds were down to earth people."

He remembers that he sometimes was invited to lunch with them.

"Mrs. MacDonald was a quiet person, frequently sitting on the cottage porch knitting and dressed as though she was going out, always wearing a nice outfit, complete with jewelry," he said. Caulkins recalled that MacDonald, although in a vacation setting, nevertheless spent much time writing.

John MacDonald died Dec. 28, 1986, at age 70 due to complications associated with heart surgery. He was devoted to our area, and certainly one of the most prolific writers of fiction ever to have called Utica his home.

Malio Cardarelli is a local historian and author. This is the fifth of eight weekly local history columns publishing Mondays in the Local section

***************************************************************************************

The MacDonald's spent their first Florida winter in this Clearwater house:

****************************************************************************************

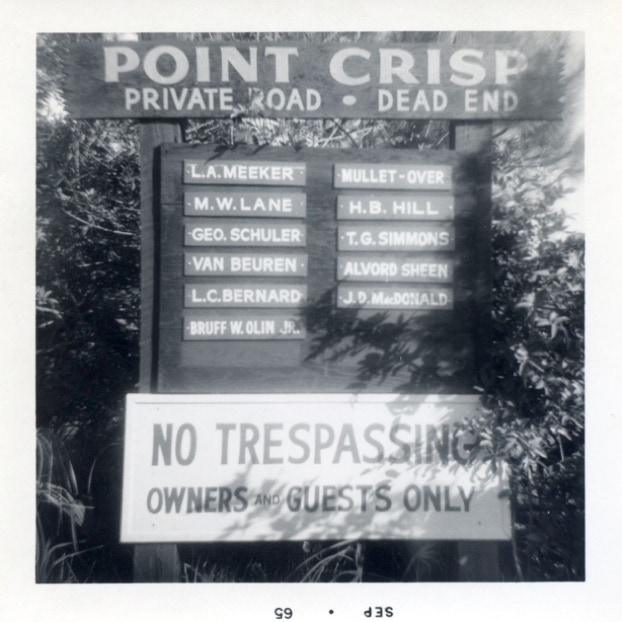

POINT CRISP, SARASOTA

From April of 1952 to May of 1969 the MacDonald’s lived during the winter in this modest home in Sarasota, Florida.

Dr. Masood Ramani, a prominent local psychiatrist,m who has since passed away,invited some of us to visit the home after the 2nd “Conference To Die For” in 2006.

SarasotaMagazine ran this in April, 2016, on the house: click on below to read the article.

The magazine has it a bit wrong: the house was finished in 1968—not 1970.

from Maynard MacDoanald

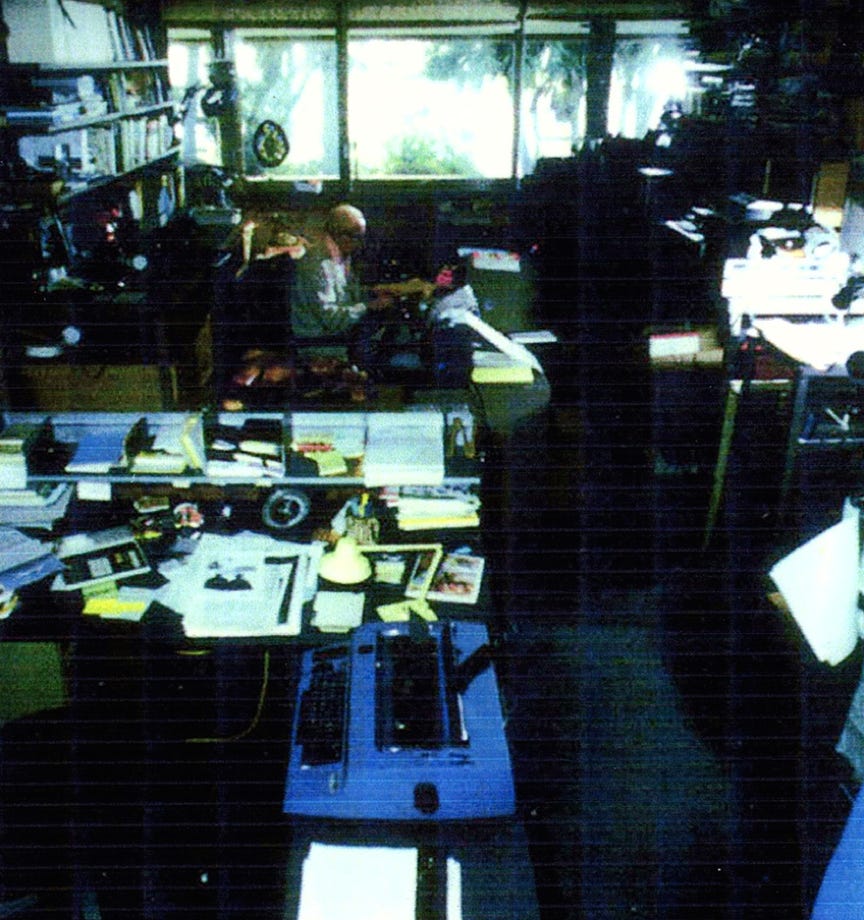

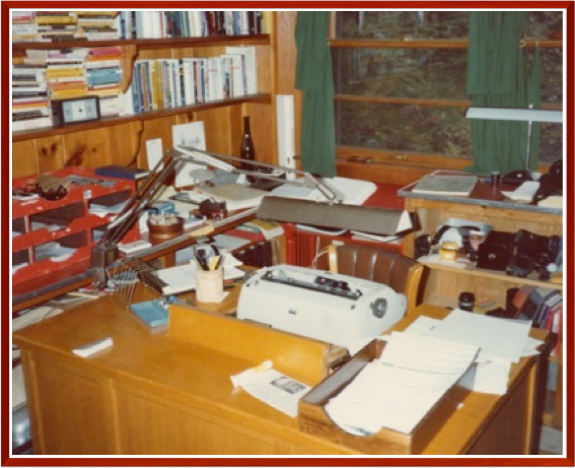

This is Point Crisp. the blue IBM Selectric typewriter certainly dates the photo. OK – you remember the downstairs layout: Lounge, veranda, kitchen. Facing the house from the seawall in front, so looking at the front door and lounge window: to the left end of the house and lounge wall were the master bedroom, my bed room and the main bathroom. The veranda is through the lounge to the opposite side of the house. Suppose you are standing in the lounge and turn right to walk into the kitchen. From the kitchen towards the rear of the house is the access to my mother’s studio which was quite a big high-ceilinged room. Through her studio was the only access to my father’s study which was up a stairway - a smaller open room over the car port. So her ceiling was very high and his study was tucked up near the roof but completely open to her studio space. He sat as shown, above the carport, the view to his left overlooking the driveway, and to his right a bird’s eye view of my mother’s studio.

There was a room at the top ofstairs flat against the wall of Dorothy’s studio. This is where the first of the McGee’s wouldhave been written.

As the area lookstoday

Maynard MacDonald says:"Yes, the outlook over the driveway is the same, but there was no veranda out there and the doors were half height windows with my father’s desk close so that he would be sitting with those windows on his left, and the stairs down on his right. The end of the room (which would have been opposite his desk) is completely unfamiliar.”

My ( Cal) guess is that ifyou draw a line from the first bookcase across the room you might have the dimensions close to what it wouldhave been. Itwould seem that someone later added the bookcase/closet area.

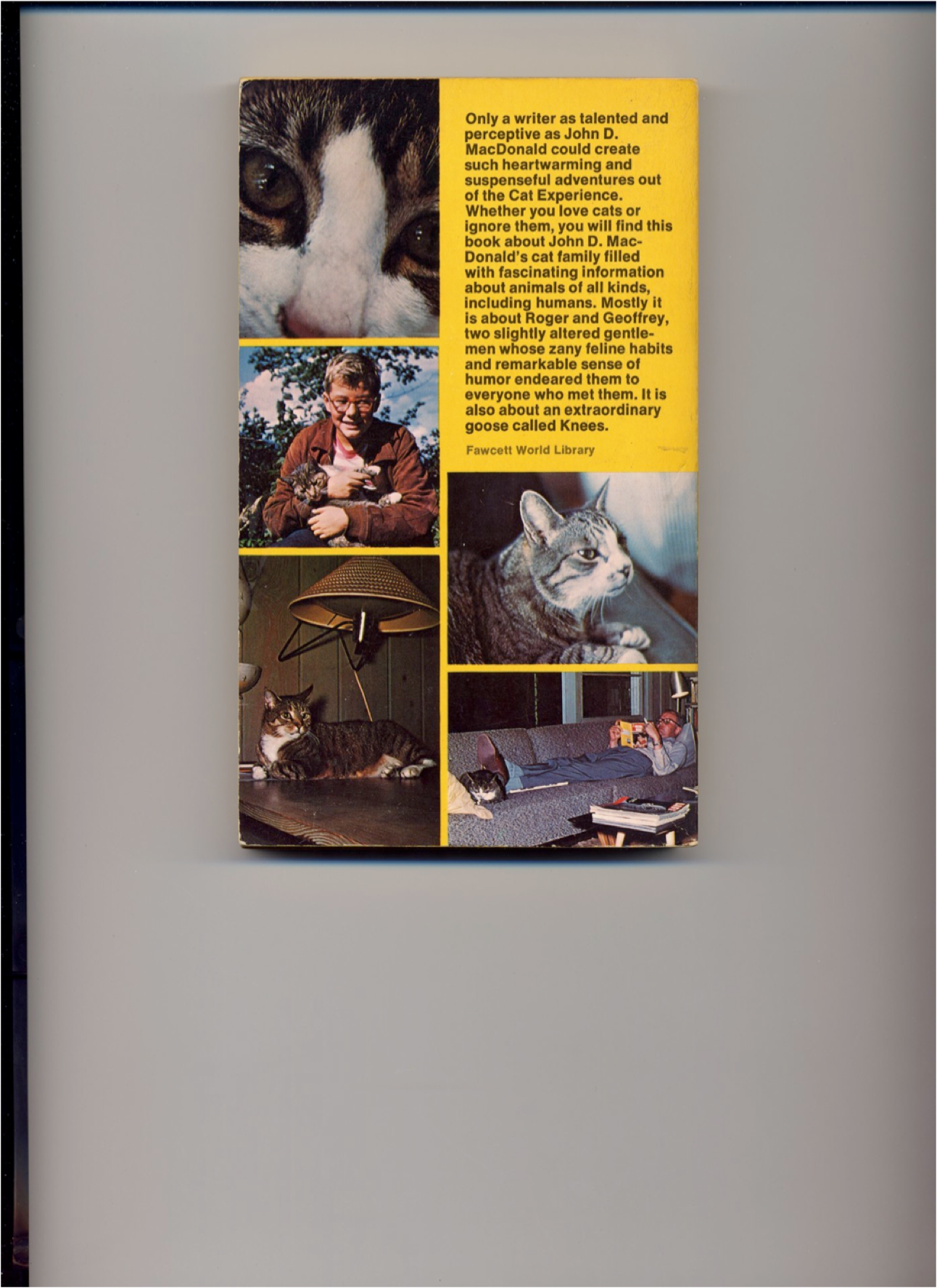

The picture below was on the back cover of The House Guests. Note the bottom right picture which shows JDM stretched out, reading, with one of the cats at this feet. The book was written in the Point Crisp home.

The compelling reason to move, as stated by JDM in early 1966:

“It became impossible for us to keep on living here on Point Crisp. The road and right of way go right past the front of the house. People we do not know have an increasing lack of respect for the privacy we need in order to work. We found a piece of property about two and a half miles from here on Siesta Key. “

(See Siesta Key home page for pictures of the home they lived in until JDM died in 1986. Dorothy lived there until her death in 1989.)

SIESTA KEY H OME

The architectural rendering of the proposed MacDonald home.

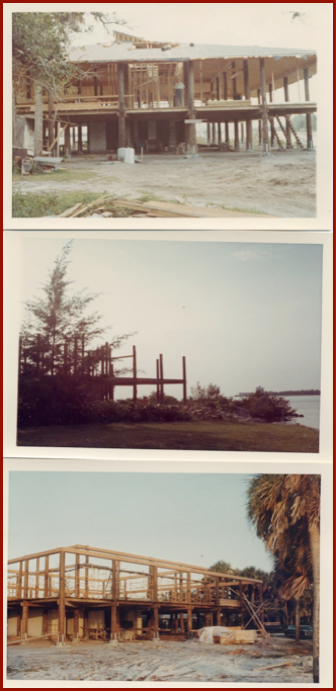

Aerial view showing house under construction.

Views of the construction early on. Note the pilings: these were embedded 10 feet into the limestone so that the house itself would withstand most, if not all, hurricanes.

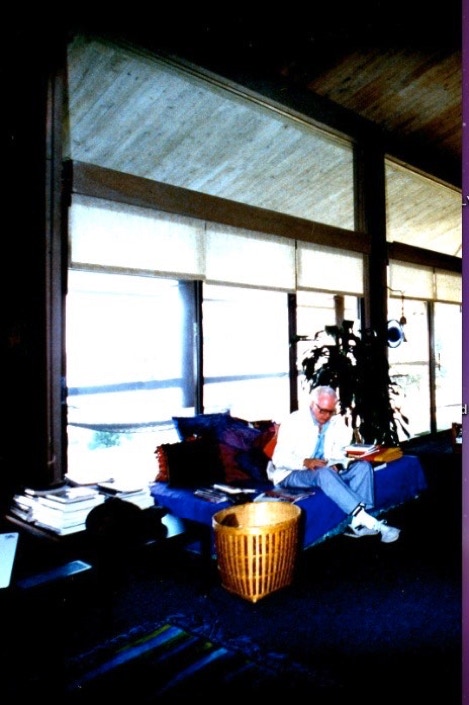

JDM at the nearly- completed home on Siesta Key.

Interior Shot

Interior Shot

note the beamswhich go down 10 feet into the limestone below grade

JDM AT WORK…(THE PICTURE FROM WHICH THIS WAS PHOTOSHOPPED WAS VERY DARK)… NOTE THE IBMSELECTRIC IN FOREGROUND

A PORTION OF THE SIESTA KEY HOME JDM USED AS HIS OFFICE--PROBABLY ON THE LEFT SIDE FACING THE GULF

Views of the rear of the property.

Taken during the 6th John D. MacDonald Conference visit to the home where a barbecue was held, and, Tim Seibert, the architect of the home gave a brief talk. Below is an article by him on the house.

Edward J. “Tim” Seibert

On August 7, 1999 the Florida chapter of the American Institute of Architects awarded the firm Seibert Architects of Sarasota their 25-year “Test of Time” award for the design and construction of a particular building within the state. The building in question was John and Dorothy MacDonald’s last home on Siesta Key, built on a private and relatively remote (at the time) waterfront site at the end of Ocean Place near Big Pass.

In 1966 when the planning process began for this new home, the MacDonalds had been living in a home near the end of Point Crisp Road, two and a half miles down the key on a small spit of land jutting out into Little Sarasota Bay. Built for the MacDonald’s in 1951-52 the house was located at the end of what was supposedly a private road that ran the length of the peninsula. But the road wasn’t gated or guarded, and anyone who wanted to could drive down the road and park in front of the house and bang on the door -- which, apparently, happened frequently.

“The road and the right of way go right past the front of the house,” MacDonald wrote in 1966. “People we do not know have an increasing lack of respect for the privacy we need in order to work.”

The design and work on the new house took three years, with John and Dorothy moving in in July 1969, and it couldn’t have been more different from where they had been living for the past 17 years. With vast, open spaces and lots of light, the house looked like no other and provided the MacDonald’s with their much-sought privacy.

On the morning of the awards ceremony the Tampa Bay Times published a reminiscence by Edward J. “Tim” Seibert, the designer of the home and owner of the architectural firm. It’s an illuminating piece with (for me) one big surprise, which I’ll address at the end. The article was preceded by a short intro written by Times “Homes Editor” Judy Stark.

A glimpse into the design processArchitecture as Art

For some people, the image of Florida is shaped not by theme parks and palm trees but by the fiction of John D. MacDonald, longtime resident of Siesta Key. His rough-diamond hero, Travis McGee, is the ultimate beach bum, man-about-the-waterfront and solver of mysteries.

McGee served as his creator's mouthpiece, speaking out in behalf of the state's ruined beauty: the poisoned Everglades, overdevelopment, building on the beaches. MacDonald crafted "strong statements about what man's greed has done and is doing to despoil our state's natural resources - statements that are just as relevant today" as they were in the mid-'60s, writes critic Ed Hirshberg.

Tonight in Naples, the Florida chapter of the American Institute of Architects recognizes Seibert Architects of Sarasota with its 25-year “Test of Time" award for the home where MacDonald and his wife, Dorothy, lived for years.

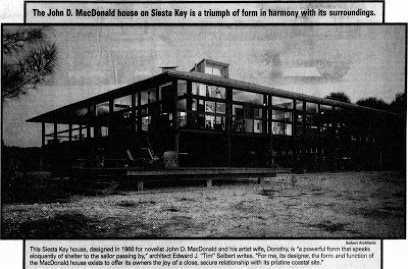

The award honors works that, by the timelessness of their design, have influenced a particular building type. The MacDonald house, designed in 1966, draws on characteristics of Florida Cracker houses, and through the use of natural materials and compatible forms becomes one with its site, preserving existing mangroves and palm and oak trees.

In this essay, architect Edward J. “Tim” Seibert reflects on the design process and his relationship with John D. and Dorothy MacDonald during what he calls “a golden time" on the west coast of Florida.- JUDY STARK

By Edward J. “Tim” Seibert

If one is going to feel romantic about a house, the John D. MacDonald residence on Siesta Key is a good choice. It stands on Big Pass, and one can look southwest to the Gulf of Mexico and northwest to the end of Lido Key, with pines filtering the view of resort hotels and condominiums. To the north and northeast, the sparkling city of Sarasota is a nighttime jewel of lights.

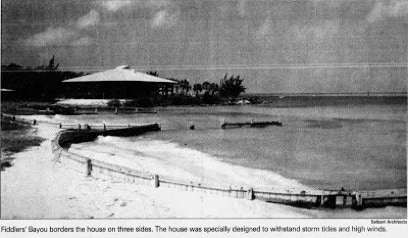

A little inlet called Fiddlers' Bayou curves in around the house, giving it water on three sides and making it potentially as vulnerable to tidal fluctuations and prevailing winds as the surrounding mangroves, oaks, palms and wild grasses. It is a structure specially built to withstand storm tides and high winds, as it has done for a third of a century now.

Approached from a boat on the gulf side, the great pyramidal, metal roof shining in the brilliant sunshine reflects the plan of the house, a powerful form that speaks eloquently of shelter to the sailor passing by. At night, the lighted underside makes the form more delicate, showing the poles and beams that hold up the 62-foot-square shape.

From the very beginning this house has been a magnet, attracting imaginative and historic interpretations: "a beautiful South Seas home," "reminiscent of the old fish houses on Florida's eastern coast," "shares many characteristics of the early Florida Cracker cottage," "a classic achievement in contemporary architecture" and on and on. It caught editorial attention in architectural and shelter publications in the United States, Europe and Japan.

For me, its designer, the form and function of the MacDonald house exists to offer its owners the joy of a close, secure relationship with its pristine coastal site. I was seeking clarity of form rather than style, with minimum intrusion into the site.

John D. MacDonald was one of America's most prolific and admired writers, completing 67 novels, five collections of stories and 500 magazine stories before he died, unexpectedly, in Sarasota in 1986. He was exceptionally quick to grasp new ideas. But until we began our work together to create the very private utopia John and his wife, Dorothy, had dreamed about for many years, they hadn't given the architecture of their new home much thought. Dorothy was a painter of abstract canvases and had studied with the acclaimed Syd Solomon, also a Siesta Key resident. My didactic nature welcomed their desire, as clients, to collaborate with me, their architect. In fact, Dorothy drew up the first floor plans.

We worked for several years on designs, beginning in 1966. The first house we designed was to be built on Manasota Key. My father, E.C. Seibert, who worked with me then as a structural engineer, got so far as building a fine boat basin at that Manatee site. John then decided he did not want to leave Siesta Key, where he had lived on Point Crisp for many years. So the project was moved to the present Big Pass site, and I designed quite a large house of heavy timber and stone, as John and Dorothy then wanted.

But as I worked along, my feeling grew that such a house would be much too massive and heavy-handed for its open, waterfront location. I was able to convince the MacDonalds that their residence should be more concise and elegant, designed from a clear geometric concept. It might also be less expensive, I advised, if it were smaller and designed in the contemporary manner. This is the concept of the house we finally built.

After my draftsman, Tom Walston, and I completed working drawings, another associate, architect Buddy Richmond, convinced me that he could make a final version that was more polished and spare, and with less expensive detailing. This final concept was drawn at office expense. John and Dorothy were such good clients, I felt they should have my very best effort. Besides, they understood and appreciated the design. Ours was the best relationship an architect can have with a client.

John and Dorothy moved into the house in 1969. For some time, as the house took shape, they had come to feel at one with the space. As the years went by, the house became more and more theirs, for both worked at home and spent the greater part of their time there. One corner of the house was Dorothy's studio, the other was filled with John's office machinery and files. Furnishings and art were not "designed" but were very much a part of the MacDonalds' lives, giving the space an authenticity that no designer can really accomplish. The only complaint I ever heard from John was that his house was so beautiful, it attracted gawkers.

My father did all the structural work for this building, which was unlike any other, at least any other built in these parts. One of the great problems to be solved was how to fasten together the uneven pine tree trunks that support the house, for they are rather like asparagus waving in the wind until you can capture them at the top. My father designed a series of specially fabricated steel connectors, which, being exposed and a design feature, were galvanized after fabrication. This was not inexpensive, and at times of such decisions, one comes to respect and enjoy an understanding and enthusiastic client.

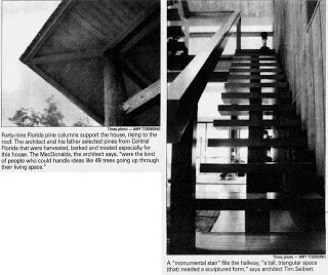

The first selection for the poles was greenheart timber, imported from Central America, carefully specified for straightness. When the trees arrived, they did not meet specs. We sent them back. This was a hassle, and again we appreciated having a client like John D. My father and I then went up to Central Florida to choose growing pines. They were harvested, barked and treated for the house. All of this, added to our "courtesy" redraw of the final plans, was not conducive to profit. But then, the idea was “architecture as art.”

It was a golden time then. We were doing something good for the sake of doing it and giving it our very best. We were happy. Frank Thyne, our builder, joined us for lunch frequently at Sarasota's old Plaza Restaurant, the favorite watering hole of resident artists and writers, many internationally known. Frank gave me a two-martini education in literature and philosophy. In return, my father and I educated him about sailboats. Frank had attended the University of Grenoble and the Sorbonne in France and had earned a doctorate in philosophy. He came to Florida in 1956 to teach himself to be a developer and house builder.

The Thyne construction crew were Mennonites, the very best craftsmen, who were proud they “could build anything an architect could draw.” Frank worried because they had an occasional habit of fasting. He made sure they ate regularly because “they tended to slow down when hungry."

The house is a strong one. As it was designed to do, it has weathered several hurricanes and a tidal wave. Each of the great Florida pine columns rests on a strong connector fitting of galvanized steel, set into a cubic yard of poured concrete, which in turn is supported by a piling that goes 12 feet down into Siesta Key's shell sand. My father also designed a breakwater in front of the seawall, made of stone riprap to absorb the force of the waves. The main structure of the house is 9 feet above the grade. John and Dorothy were the kind of people who could handle ideas like 49 trees going up through their living space. This stormproof house was built a good 10 years before the federal government made up all the building codes of today. The concept of a house that could withstand natural beachfront forces was a new idea then.

The 50-foot-square living space and the 12-foot surrounding porch have a constant roof slope that starts at 8 feet on the porch perimeter. The porch has a 4-foot overhang for tropical downpours. At the glass walls, 12 feet in from the porch edge, the roof is 12 feet high. It rises to some 22 feet at the center. It's a grand space, as only one bedroom and bath and the entry foyer have walls that touch the ceiling. The ceiling is structural deck, consisting of two layers of pine for strength and one layer of cedar. On top is a triple layer of insulation, over which is the galvanized roof.

Cut into the pyramid of the roof was a sun deck. I mention this to show what an understanding client John was. Perhaps people who write books understand the problems of composition with which others must struggle, for John was fair of skin and didn't sunbathe. However, he agreed that the deck was a place for a monumental stair to be built from the main floor hallway below. The hallway, a tall, triangular space, needed a sculptured form, the stairway, to fill it. Later we roofed over the sun deck, and John serendipitously had a rooftop writing room. Problems like this were solved in laughter and understanding friendship. John was a man of quick wit and high humor, and I miss him.

For me, this glass pavilion provides the ultimate visual extension, the architect's art of using the transparency of glass to extend the interior experience outward while bringing the surrounding landscape inside, making it a part of the interior landscape. From this strong, safe glass shelter, one becomes part of a soft, starlit, tropical night, the clash and flash of a thunderstorm, the wonderful serenity and soft dawn light of early morning.

Edward J. "Tim" Seibert's firm Seibert Architects is in Sarasota.

PISECO LAKE

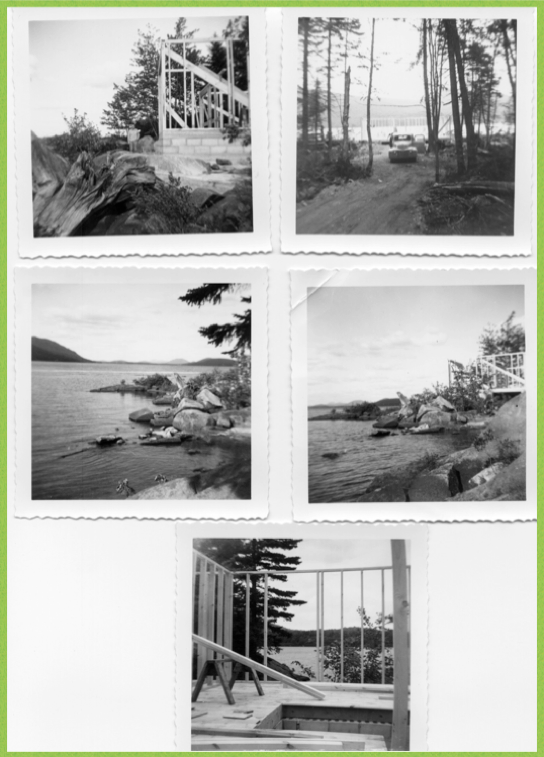

JDM and Dorothy stayed at this camp,which they built in 1949. It was located in Piseco Lake, north of Utica, in the Adirondacks. They spent many summers there for the rest of their lives.

There are hundreds of pictures of the camp area in the Collection taken by both JDM and Dorothy while in residence.

(Please note: these are duplicates from the Collection, and should not be copied and distributed.)

Shown in the picture above are Dorothy and her brother, Sam Prentiss. The cabin has been sold and is being renovated. Originally there were 12 small rooms in 1200 square feet of space, including a small room in the attic.

One of those rooms on the main floor was JDM’s study, see below the cabin picture.

The desk and typewriter (one of many he used) may be donated to the Collection by Brad Dake, the new owner. Note that the desk faces inward, not out, which JDM preferred so that he would not be distracted from writing.

Above: the garage

To get to the cabin one must turn off the main road onto a fairly twisty dirt road through the woods. You have a feeling that visitors--other than family-- were not encouraged. The garage actually faces the front of the cabin.

\

The rocks are very close to the back of the cabin. See Piseco Lake 2 for more pictures.

Below are some black and white photos taken in 1949 of the cabin construction.

The front of the cabin has been changed considerably.

The rear of the cabin faces Piseco Lake, and is only about 50 feet from the water.

New owners Darla Oathout and Brad Dake,

Also pictured: Nola Branche

A view of the lake from the back of the cabin.

Winter and Fall views of the cabin.

JDM and Dorothy took many pictures of these two Piseco scenes over the years.

(see also JDM as photographer)

In Cl

© bill 2014